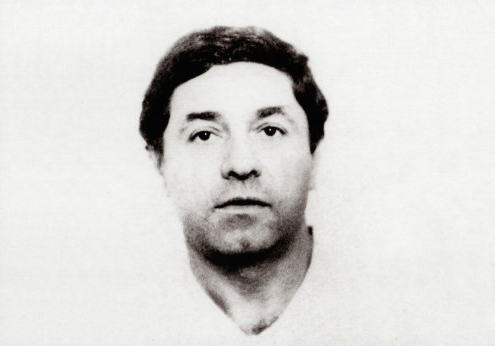

This morning Stevie Flemmi is seeking “compassionate relief” from his murder sentence in Florida – one of 50 murders he has admitted taking part in “either as an actual participant or the conspiratorial aspect.”

Fifty murders!

And now the Rifleman, as he was known in the Boston underworld, wants… compassion.

Not going to happen, of course, because even in the extremely unlikely event the Florida parole board decides to cut him loose, Flemmi is serving a concurrent federal life sentence for 10 of those 50 murders, not to mention another concurrent state sentence in Oklahoma for yet another contract hit in 1981.

The telephone hearings start at 9 a.m., and Stevie is number 20 on the list of petitioning jailbirds. He’s a serial killer’s serial killer. How will the parole board handle such an outrageous request?

Probably very quickly, and very perfunctorily, although it would be nice to get some sound for my radio show later in the day.

Stevie is 87 years old now, and you can understand why he’s taking this longest of longshots. I mean, what’s he got to lose?

Every other violent thug in state and federal custody has asked for “compassionate release” since the Panic began last year.

Take a guy named Eric Reinbold in Minnesota. At age 44, he’d already had the virus when he was let out of Club Fed in April on a compassionate release. His family said they would “ensure that he stays law-abiding.” Less than four months later, Reinbold is back in prison, charged with stabbing his wife to death.

Since his arrest in 1995, Flemmi has always dreamed of getting out someday. Hope springs eternal and all that.

During Whitey Bulger’s trial in Boston in 2013, one of Whitey’s lawyers asked Flemmi if he thought he would get ever be sprung.

“I’m still alive,” he said with a shrug. “There’s always a hope. You never know.”

Three years ago, Flemmi was back in Boston, testifying against another one of his old underworld pals, Cadillac Frank Salemme. In court, Salemme would stare at his longtime partner. Frank would shake his head, occasionally turning around to the reporters while rolling his eyes in disbelief.

“You know he still thinks he’s getting out,” Frank told us one day during a break. “He’s still telling people that.”

If there is any conversation this morning about Flemmi’s petition, I hope the parole board asks him, or his lawyer, about that estimate of his of 50 murders, which he made three years ago during the Salemme trial.

On cross-examination, that was the first question Frank’s lawyer, Steve Boozang, posed to Flemmi.

How many?

Stevie had to consider that one. He took his time, pondering, adding up the numbers in his head. It was a tough question, obviously.

“Well,” the Rifleman finally said, “considering (Whitey) Bulger’s murders, (Johnny) Martorano’s murders, Winter Hill’s murders, (Wimpy) Bennett’s murders – that’s a lot of murders.”

Too many murders to even have a shot — bad word, excuse me — of getting out. But then, his life could be worse. It could be over, like it is for at least 50 people, including women, who Stevie used to know.

As a government informant — a rat — Flemmi is in what the federal Bureau of Prisons calls WitSec — Witness Security.

It’s a special program for, uh, cooperating witnesses who are at least theoretically in physical danger because of their testimony. The locations of WitSec inmates are never released. You won’t find Stevie’s name on the Bureau of Prisons inmate-locator website.

A WitSec alum once told me he’d hated doing time with professional snitches — “all of ‘em would rat you into another thousand years on your sentence to get a day off their bits. So you can’t talk to nobody.”

Stevie, on the other hand, is doing life plus 30 years. So what’s another thousand years, more or less. And WitSec pens have a reputation as being at least somewhat more pleasant than your normal prison.

Stevie doesn’t do well on cross-examination. He gets flustered and starts stuttering. During Whitey’s trial in 2013, lawyer Hank Brennan asked him if he was in a WitSec facility that had a delicatessen.

“That is absolutely ridiculous,” Flemmi said.

“Can you get rib-eye steak?” Brennan asked, and Flemmi glared back at him.

“If I gave some of that food to my dog, he would bite me.”

Brennan knew he was getting under the Rifleman’s skin.

“On Memorial Day and the Fourth of July,” he continued, “they celebrate with hamburgers and hot dogs and watermelon, don’t they, Mr. Flemmi?”

“You know something?” Stevie said. “The hot dogs were burnt, the hamburgers were burnt.”

And now he’s looking for compassionate relief. Parole board, what more do you need to know?