No good deed goes unpunished — if there was one lesson Howie Winter learned in his 91 years of life, that had to be it.

In the early 1970s, Whitey Bulger was on the Hit Parade in Southie. He was being chased all over town by the Mullens. Howie straightened it out for Whitey, and even brought him into what became known as the Winter Hill Gang.

A few years later, Stevie Flemmi wanted to come back from Montreal, where he’d been on the lam since blowing up a lawyer in the man’s Cadillac in Everett.

The only witness against Stevie said he’d recant — if Howie would buy him a truck. Howie bought him the truck and Stevie triumphantly returned to Boston.

And Stevie joined the gang too, which was even more selfless of Howie, because Stevie had once planted a bomb in Howie’s car and came damn close to blowing him up.

Two good deeds for two very bad guys. And what was Howie’s reward?

Within five years he was on a treadmill from one prison to another, as his two good buddies endlessly ratted him (and everyone else in organized crime) out to the FBI.

But Howie died a free man Thursday night, in Millbury, in his own home.

For more than a decade, Howie was The Man in Boston. He fixed horse races, owned strip clubs and garages, hijacked trucks and hung out with major celebs like Robert Mitchum and Bobby Orr.

His Winter Hill Gang essentially merged with the local Mafia, In Town as it was called. One night in 1981, the feds recorded the number-two guy in the Boston Mafia lecturing a small-time hood who’d stolen from the Hill.

“Did you know that the Hill is us?” Larry Baione explained. “Maybe you didn’t know that, did you?”

“No, I didn’t,” the terrified hood responds.

“Did you know Howie and Stevie, they’re us. We’re the bleeping Hill with Howie. You didn’t know that?”

Notice, Baione didn’t mention Whitey. Bulger was small potatoes until he figured out how to get rid of Howie. No good deed …

Howie used to say that he survived two big wars. First World War II, during which he enlisted in the Marines in 1943 at the age of 14. And then the so-called Irish Gang War of the 1960s, out of which he emerged as the top dog in Boston’s non-Mafia rackets.

Howie’s life story would have made a fascinating book. There was only one problem: You would have had to skip over large parts of his career, for the simple reason that there are some crimes for which there is no statute of limitation, if you get my drift.

For obvious reasons, he never liked to talk about the … wet work, shall we say. I finally got Howie going on the hits in February, the last time I ever sat down with him. It was a start, but then came COVID-19, and the election, and we never got back to it.

Howie called me a couple of weeks ago. He’d been concerned about what he’d said, and I told him there was nothing I could do with it, anyway. At least not as long as he was alive — although I didn’t tell him that, obviously.

I did do one podcast, about his life with his wife, Ellen Brogna. It gives you a flavor for the period, I think. It’s the final of our “Dirty Rats” series. You can find it at howiecarrshow.com.

Howie always said that the original Winter Hill Gang was just three guys — him, Joe McDonald and Buddy McLean, who was the real boss. Buddy got shot on Broadway in the waning days of the gang war, and it took the Hill a year to track down his killer, Stevie Hughes.

They caught up with Hughes on Route 114, then a rural road in Middleton. He was driving a car with another guy, who had brought his two Chihuahuas along for the ride.

Hughes’ car, a Pontiac Tempest, was riddled with bullets when State Police found it in a ditch with the two corpses. The two Chihuahuas had survived, however, and were playing in the grass next to the wreck.

“I was so happy the dogs were okay,” Howie said with a chuckle.

Once Whitey and Stevie figured out there’d be more money for them if Howie and the rest were gone, they started snitching to the cops.

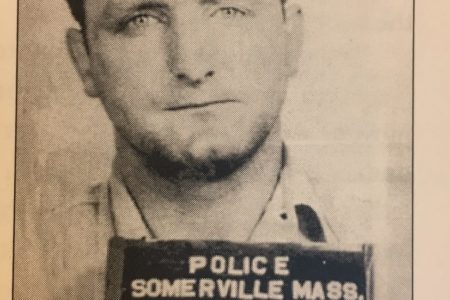

Howie’s first rap was a state beef, involving pinball machines. The evidence against him was so overwhelming that Howie decided to take the stand in his own defense.

The prosecutor asked him about the fact that he had about a dozen different addresses, and next to no visible means of support.

“Do you live in Somerville?” the prosecutor asked Howie.

“Sometimes,” he replied.

“Did you live there last night?”

“No,” Howie said. “I did not.”

Howie was convicted, along with one of his guys, Sal Sperlinga. Before the sentencing, Howie wrote a note to the judge.

“I respectfully request that in considering sentencing for Mr. Sperlinga, Your Honor keep in mind that he never had much to say and that he never raised his voice and also that he is the sole support of his 82-year-old mother.”

The judge told Howie, “I respect you, Mr. Winter, for the motion you filed.”

Sal got a reduced sentence and was soon out on work release. He was playing cards with a Somerville alderman when a junkie he’d told to stay out of Magoun Square came up and shot him dead.

No good deed goes unpunished.

Rest in peace, Howie Winter.